UV

Cured Finishing for Guitars

By Brian

Howard, luthier

Magnolia ,

DE

I have been finishing wood my whole life. Part of my business for several years

was contract finishing for small guitarmakers all over North America and I still offer complete finishes on a limited scale. As such I

was very well versed in all manner of sprayed finish systems like Conversion

Varnish, Epoxy Urethane, Nitro… And I must say that all that experience was

only of limited use with this material and system. I do however feel this is

the future, soon shops will be limited to CA repairs and water based systems for complete finishes (which

really do not work well on guitars in my opinion) or they will need to go UV.

So I have prepared this article to help guide you into the world of high

quality and acceptably thin UV cured guitar finishes.

There are a few things to understand first. These systems are rarely

ever solventless (100% solids). They are far from odorless though there really

aren’t any toxic fumes (smells like fiberglass and hot plastic). As with any

spray finish, atomized coating should never be inhaled. They also do not cure

instantly.

The first thing you will need is equipment. This will consist at the

least of a UV curing lamp, safety gear and decent spray capabilities. I do

recommend an explosion proof fan because while these systems are touted as

solventless that is not always completely the case so better to err on the side

of caution! There are a few companies offering curing equipment and most of the

standard offerings are handheld or designed for mount over a conveyor belt. UV

“ovens” like those used by PRS and others have become more available but are

expensive and usually configured for a certain model of guitar . Here I use a handheld

system made by UVIII called the Cure Buddy. This is the minimum set up for this

work and is very simple. A ballast and an emitter. Shown here is my setup and

the required safety gear. Yes the welders gloves are needed, not just to shield

from UV rays but heat as well, the emitter gets very hot!!

***SAFETY NOTE, UV RADIATION EXPOSURE

MUST BE TAKEN SEROUSLY!!! ALL EXPOSED SKIN MUST BE PROTECTED. YOU MUST DRESS

VERY MUCH LIKE A WELDER TO PROTECT AGAINST THE RADIAION!!! EXPOSED SKIN WILL

GET RADIATION BURNS!***

UV emitter and ballast

Safety gear

There are different types of UV cure materials available and almost any

polyester blend can be made UV curable by adding a photo-initiator. You want a

system engineered for musical instruments and not floors or boats….. those are

usually made with little regard to achieving a thin final film and will have

vastly different flexibility than we want here. Even then there are a multitude

of choices. There are UV only and dual cure systems. UV only must be cured by

correct UV exposure. Dual cure will continue to chemically cure after exposure

ensuring complete curing but will typically not completely self cure without

UV. While dual cure solves one problem it introduces new ones like needing to

clean equipment immediately, the need to mix components and storage of catalysts that will

completely kick off if any dust or contaminate gets into the container. UV only

on the other hand means your exposures must be absolutely complete! Uncured

material at the bottom of pores etc will cause problems a few months down the

road. In the end after trying both I opted to go with UV cure only and skip my

perceived hassles of the dual cure system.

Your finish system will start with an isolation sealer of some sort to

seal oily wood usually called an “Isolante”. This is critical on any oily wood

and recommended for all work no matter species. Any oil present in the wood

will cook out into the finish during curing if this is not used. It does not

matter that the surface was cleaned directly before application. These wood

oils can affect curing, clarity of the finish and adhesion. There are UV

versions and chemical Cure versions I use a chemical cured two part in this

article and we start with that coat already applied as it is a straight forward

spray sealer application. Follow your manufacturer’s instructions here.

This is scuffed with 220 paper to knock down any raised grains and

de-gloss the surface. This coat is typically thin, .5 mill on average so be

careful not to sand through or you must reseal! You may think you want a finer

grit here….. You do not! These materials are all solely dependent on mechanical

anchor between coats. Fine sanding will lead to de-lamitations and blisters down

the road in curing of subsequent materials.

Now we proceed with the pore filler. I am

using a Cardinal product here. This product is a thixotropic jelly. I tend to

like this product for its ease of application without a sticky mess though it

is a bit more finicky to cure than some of the others I have tried. This

process will take 3-4 coats on average wood and wood with deep grain like swamp

ash can take 6 or more. Somewhere in the marketing lit or perhaps a salesman

told you this is a 2 coat process….. And maybe, if you really glop it on extra

thick. But we want thin finishes!! So we must take time to build the filler up.

Another reason to not do 2 thick coats is the sanding. While the product sands

incredibly easy when applied thick it must be sanded back hard. This leads to

sand through and bare wood which must be sealed with isolante again and

sometimes re-filled. This can become a vicious feedback loop costing lots in

extra time and materials.

The first major difference between

conventional finishing and this system comes up now. Unlike other finishes

where the entire instrument is done at once here it is much better to work on

one surface/section at a time. This is an acoustic so my sections are back,

treble side, bass side & neck. I do electrics in a very similar manner.

Concentrating on sections like this makes application less messy and makes

complete curing with the emitter easier. This routine will be used all the way

through the clear coats as well.

For application of the filler I use a plastic spreader like for bondo.

The key is keeping the edge keen by trimming it as it wears. Wiping it on with

a cloth or paper towel at this point tends to lead to bits of rag fiber trapped

in pores. A bit of jell is scooped up and spread evenly across the back

For this first coat final spreading should be done with the grain and

using the spreader at a low angle drag it out as smooth as possible. You mainly

want it in the pores with the surface looking kind of wet. A few light trails

from the edges of the spreader are OK here.

Now it is time to cure. Most think this process is instant, I know that

was what I expected. It is in fact not…. The back will take 4-5 minutes to cure

as will each of my designated sections as they are about the same area as far

as UV light is concerned (see diagrams under Clear coats). This is the main

reason to break the work down into smaller bits. Waving a UV wand steadily and

evenly over every surface of a guitar for 20 minutes at a stretch tends to lead

to uneven curing due to fatigue, both mental and physical. Not to mention the

gyrations needed to climb under and around a hanging guitar to get even

exposure on every surface.

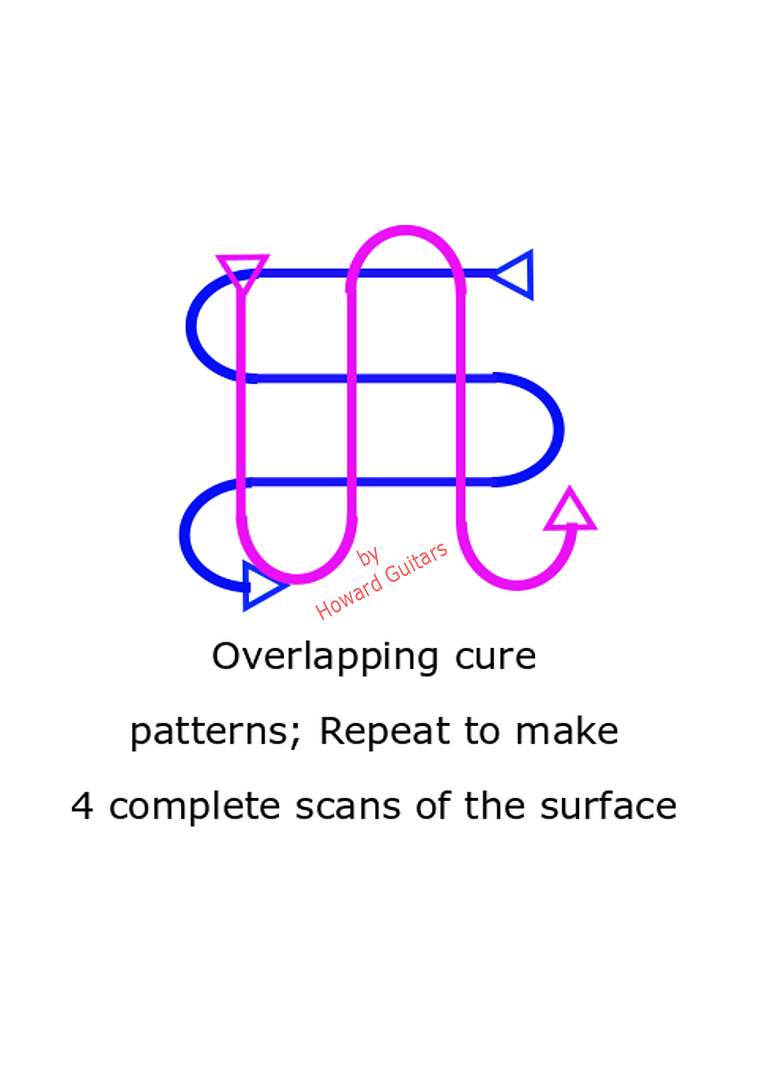

The following curing process is used

at every stage of the finish.

The emitter has a curing foot print determined by its size, power &

distance from the surface. To get the most even cure the quickest I have

developed what I call the “4-Spray” technique. I use the emitter as if it were

my spray gun and apply my rules of “4” which are;

Using a pattern just like you would

with your spray gun with minimal pattern overlap go back and forth over the

surface and then up and down. You will scan the surface 4 times, twice E-W and

twice N-S. You will do this at approximately ¼ the speed you would normally

move a spray gun. This will take at least 4 minutes. Do not get the emitter any

closer than 4 inches to the surface ( 6 inches works very well).

If you have a decent sense of smell you will smell it when the filler finishes

cooking off. That is due to the heat generated by the curing process. All the

UV radiation is converted to heat as the components link. At this point the

surface will be quite warm to the touch! You do not need your gloves to touch

it but you should be able to run a finger in your leather glove across it and

not leave a mar. If it leaves a mark of any type, the smallest smudge, you are

not done curing. This will take practice and is especially important in the clear coats.

Curing times are not set in stone. There are differences in materials

and how they cure. Some materials cure quicker and easier as thicker films and

some as thinner ones. This something you will need to learn about the materials

you chose. Also the color of the wood underneath the finish and whether it

absorbs or reflects UV radiation will have an effect on curing times as will

any toners or dyes used such as sunbursts etc. Ebony for example absorbs UV and

therefore makes the coatings take longer to cure. So watch for this on

fretboard edges etc.

Now back to the process itself. While the back cools I will apply to

another section and cure it repeating until all sections are done. Now the

surface is scuffed again with 220 using a cork lined or felt block. Only a bit

of leveling on any ridges left from the spreader. Again, careful not to sand

through or you need to reapply isolante! Cleaning between operations is done

with a vacuum using a brush attachment and a china bristle brush. Compressed

air as long as it is clean and dry may be used as well. Wiping with solvent

will drive sanding debris into partially filled pores and gaps at bindings

which will be white when finished. In

the case of this mahogany which is very average you can see how the grain needs

a lot more fill in areas.

We now have established a base to work from. The next coat is applied in

the same manner with an additional step. After spreading the jell I use a clean

folded white paper towel and mimic sanding in a circular pattern. Not really

wiping any jell off but spreading it out evenly. Here I show the amount

actually wiped off at this point. You can still see a lot of grain and some

minor ridges at this point.

This then cured again and sanded at

220. You will be tempted to think you can actually level sand this and apply

finish but invariably a sand through will happen and you will get set back. So

another coat is applied in the same manner as the second.

At this point be on the lookout for thin spots after wiping. They will look

slightly dull. These will likely be sanded through when you level out next Here

is one such spot by the edge just above the glare.

The surface should look like it was evenly sanded at this point before curing.

After this coat you may start to level sand carefully. While some spots

are fairly thick the pores and

grain may still be a bit low. This mahogany had some reverses in the grain that required a 4th application to get to a point it could be completely level sanded. Attention to detail here is critical. You want to get all grain and defects filled now! Small holes in your filler will repel the clear finish when you spray it. This is what we should have when ready for top coat.

grain may still be a bit low. This mahogany had some reverses in the grain that required a 4th application to get to a point it could be completely level sanded. Attention to detail here is critical. You want to get all grain and defects filled now! Small holes in your filler will repel the clear finish when you spray it. This is what we should have when ready for top coat.

Clear Coats

In this article I am using a clear coat from

Hentzen Aerospace, their PST908, it is the same as Taylor uses at their

factory. These UV top coats are different than anything you are likely to have

worked with including peroxide cured polyesters. They behave very different.

Unlike other polyesters they are not really thixotropic so they gain no flow

out from agitation via atomization. They are relatively thin viscosity for

something that is 75% + solids but have very high surface tension. The result

is a coating that is both prone to runs and exhibits lack of surface flow. For

a spray finish that isn’t typically what you want. The high solids do however

make up for this as so few coats are needed to get the job done. The high

surface tension will cause the material to gather at any edge and this is why

holes in the filler become almost impossible to deal with, they are surrounded

by edge.

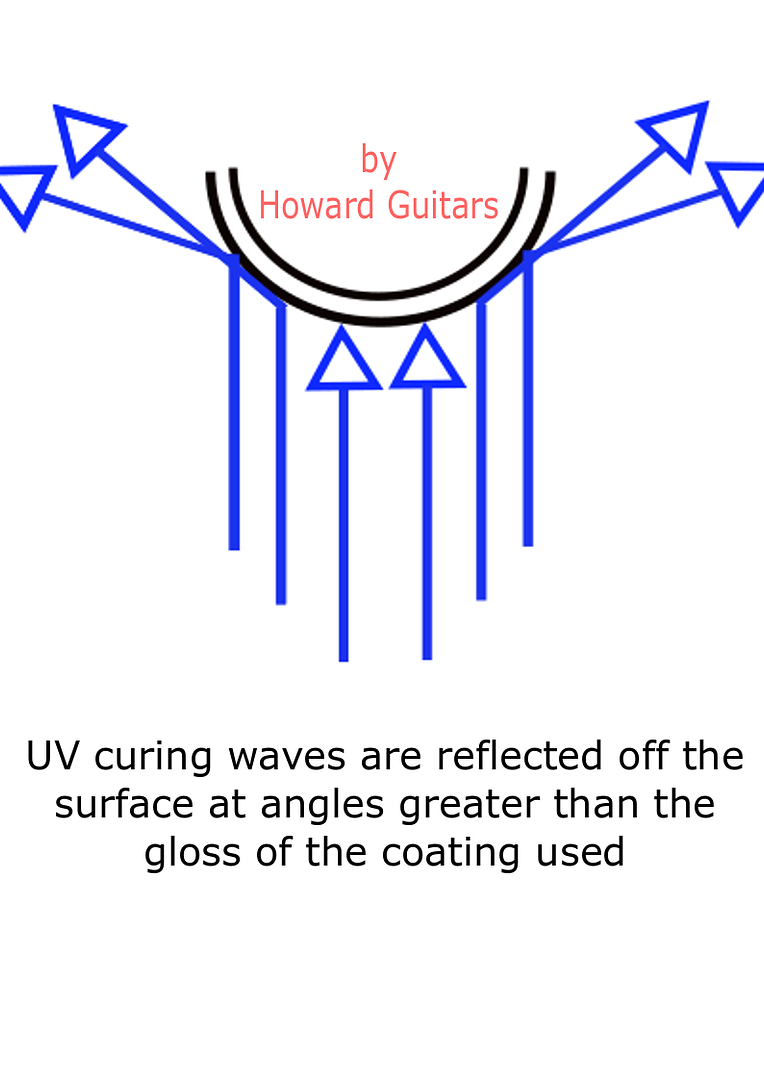

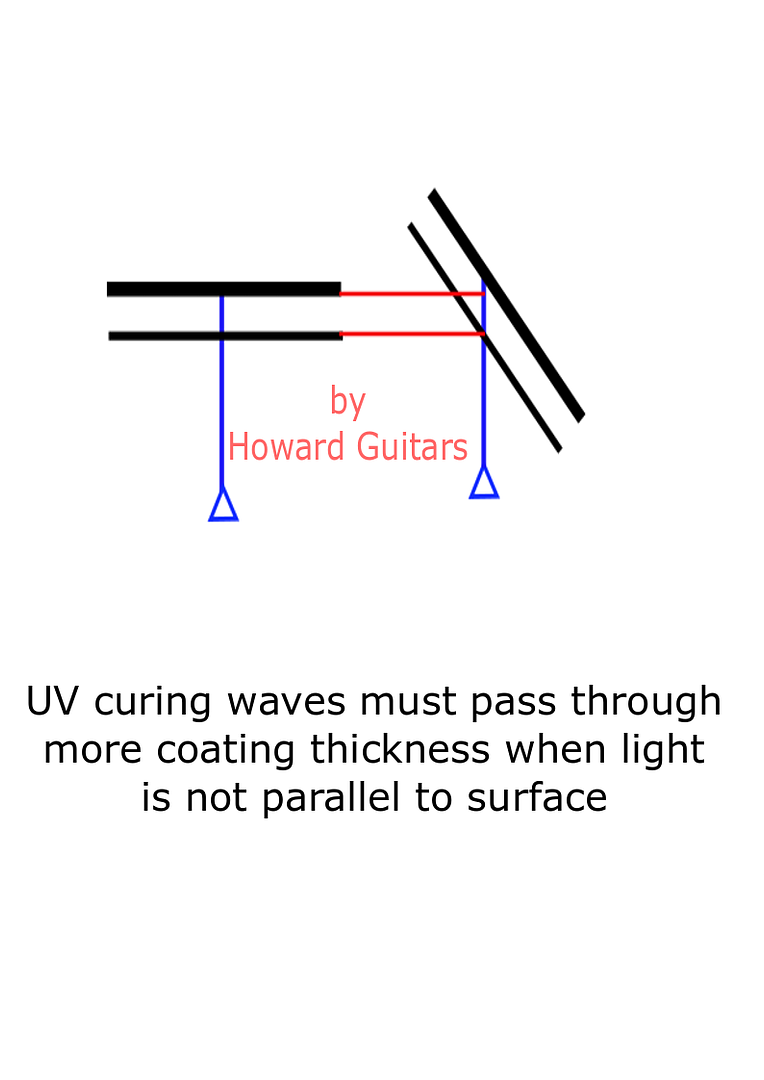

Curing clearcoats will be the same process but

the materials will act a bit different due to increased gloss and other

variables in formulation. Surfaces like the back and top of a guitar are

relatively easy and straightforward to cure. Sides and necks become a bit

tricky. Even curing here can be tough to achieve! This because the UV radiation

will impart energy into the coating only at close to a 90° angle. As angle

skews the surface becomes reflective and the UV bounces off! How much this

affects your coating will depend on the gloss of the coating. Another thing

that works against us when the light is not directly 90 °to the surface is the

fact that the coating appears thicker to any light that does penetrate upping

the exposure needed further still. This makes the waist and shoulders of the

body deceptively difficult to completely cure. This is also true of the neck.

Cutaways can be very tough when the neck is attached. My “4 Spray” curing

pattern helps assure maximum and even exposure.

While we have been solventless up until now, that is not the case

anymore. All of these systems use some solvent, sometimes pre packed and

sometimes added as needed. Just because it says VOC free only means free of

restricted or regulated VOCs, not all VOCs!! In the case of this material I add

the solvents as needed as I have done with all other finishes. MEK is the basic

solvent used and is good up to an 80° F spray environment. It is also the

recommended clean up solvent. The solvent used here is less than 10%. Just

enough to get decent atomization. Do not confuse atomization with flow! Over

reduction in an attempt to gain flow will result in a runny coating that cannot

be applied at a satisfactory build per coat. Judge atomization by droplet size

at impact.

Again I use my 4 sections but this time I start with the sides as this

makes clean up later easier and uses less solvent for that. I am using a

gravity feed HVLP Devilbiss gun with a 1.3 needle/tip and a standard aircap.

About 25 PSI flow through the gun when triggered and set for a 4 inch pattern

at 4 inches. I spray one coat exactly like any other material only slightly

thinner, about 2 wet mils. Wait 10 minutes for solvents to evaporate and the

coating will jell slightly. Spray another thin coat and wait another 10

minutes, then cure as before. The second coat here is very difficult to see the

spray pattern on so working in a robotic fashion when spraying is recommended. In

this manner build per cure cycle can be increased without compromising

inter-coat bonding and flow out increased. Once the sides are done the top and

back can be done at the same time to save time. And then finally the neck. Make sure to wait on the evaporation before

curing or you will get pinholes that will repel the next coat.

NOTE

Different brands of coatings will have varying

amounts and types of solvents you may need to adjust your flash times accordingly,

especially before curing. Some manufacturers also recommend stacking all the

coating and curing once. I highly recommend against that as it leads to sags

and increased build at the edges which can be problematic to sand out prior to

buffing.

A few words about spraying and curing

the different designated sections. After the sides are done and the top &

back are sprayed there will be some overspray that clings to the sides. We must

deal with this. This very important as all inter-coat bonds are mechanical!

There are two options for this and I will present them both. Each has its own

perils…..

1; We can deal with the by wiping it off with clean paper towels and

some MEK. Note this is done prior to any sanding! Once you start sanding do not

wipe with solvent, if you missed a bit of overspray with this method work it

off with some scotchbrite. Otherwise it will gum up paper and put heavy

scratches in your finish.

2; we can cure it with the UV but must

then be sure to sand it all off when we prep to re-coat or buff or you may have problems

with surface texture returning after buffing or grey spots in your finish. This method increases the sanding

needed to prep which can lead to sanding through to the filler if

you are not careful. Remember I am working to get the thinnest film possible.

My personal choice is a combination of

the two, wipe down between clear coats and cure & sand after final clears.

After the first set of clears we have approximately 1-1.5 mills of filler sealer and 3 mills of

finish. This is now scuffed again with 220. I know some of you are thinking

this should be much finer but in this system that is not the case. Sanding too

fine between coats can lead to witness marks between coats when buffing. Keep

the sanding light but rough and quite thorough here. Make sure to get the

surface build at the edges. You can go over this with maroon Scotchbrite a bit

to remove any glossy spots in the spray texture that remains.

Another two coats of clear is applied exactly as before. If everything

went well we are now ready to level and buff the surface at this time. This is

not really the standard we are used to either. This material has a preference

for being sanded fine before buffing. I use an arbor and Menzerna

compounds and most other coatings need no finer sanding than 600 to begin the

buffing. This coating likes to be sanded at 1000 before I start with P204.

Thankfully one of the characteristics of this finish is easy dry sanding. I

have never been one to wet-sand a guitar….. water causes the wood to swell and

then the pores ghost back through very quickly. I start at 400 grit and sand

75% flat and then work up through 600, 800 & 1000 ending with a perfectly

flat surface. From here the buffing goes very quick and easy.

This method yields a 5-6 mill thick clear finish very consistently. It is tough but light, non yellowing and will not cold check.The entire process can be completed in a single day and it is very repairable quite quickly and easily with this same equipment and materials. Welcome to the future of guitar finishing.

This method yields a 5-6 mill thick clear finish very consistently. It is tough but light, non yellowing and will not cold check.The entire process can be completed in a single day and it is very repairable quite quickly and easily with this same equipment and materials. Welcome to the future of guitar finishing.

For those interested in a more in depth

understanding of this process I offer one to one hands on instruction here at

my shop. For info on that please contact me directly at Howard Guitars or call (302)310-2035

thx bri

ReplyDelete